Photo Journal: Growth and Branch Development 1

This week I thought I’d follow up on the last paragraph of this older post that had been getting some recent attention, as well as my comment under that post.

Fig. 1 below is the very same Lang referred to. This photo was taken on 19th October 2018, about two months after being potted into a 30 cm pot in August 2018:

Lang jujube tree, 19th October 2018

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

Fig. 2 is the very same Li also mentioned, again two months after potting in August 2018, and photographed on 19th October 2018:

Li jujube tree, 19th October 2018

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

Both trees are of similar age, and you can see why I described the Li as ‘runty’ in that comment! It looks rather lost in that pot…

Fig. 3 below was taken a bit over a year later, on 7th November 2019. These are the same two trees in Figs. 1 and 2, side-by-side. The Lang (Fig. 3, left) and Li (Fig. 3, right) are in the same 30 cm pots of August 2018, and had been watered and fertilised similarly the whole time. They had otherwise not been disturbed (though I will pot them up next winter 2020).

The Lang at time of photo was about 110 cm high from base of trunk to tip of leader (longer if accounting for the angled growth), as marked. The Li was about 75 cm as marked (and longer again if accounting for the very angular growth!).

Different growth responses of two similarly-aged jujube trees.

Lang (left) and Li (right), both potted in August 2018.

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

And Fig. 4 is the same photo, but showing how each tree had grown (or hadn’t!) by mid-spring 2018 and mid-spring this year 2019:

Growth by year

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

The Li is growing exactly as the Ta-Jan and Adrian’s Chico did. That is, it wasn’t, and then it was, with gusto!

But why was the growth of the Li (and Chico) so different to that of the Lang? To find out, we will need to zoom in closer on various branches and examine them —and if you’re not familiar with how these trees grow you are about to learn quite a bit!

But first a brush-up on some terminology to make this easier. Common to plant stems, irrespective of species, are nodes, the points from which leaves and branches grow. Some nodes are really distinct, such as the thickened rings between the segments of bamboo stem. (The botanical term for a segment of stem between nodes, regardless of species, is internode.) As leaves and branches grow from buds, buds are thus found in the nodes, whether or not they actually go on to grow a leaf or a branch.

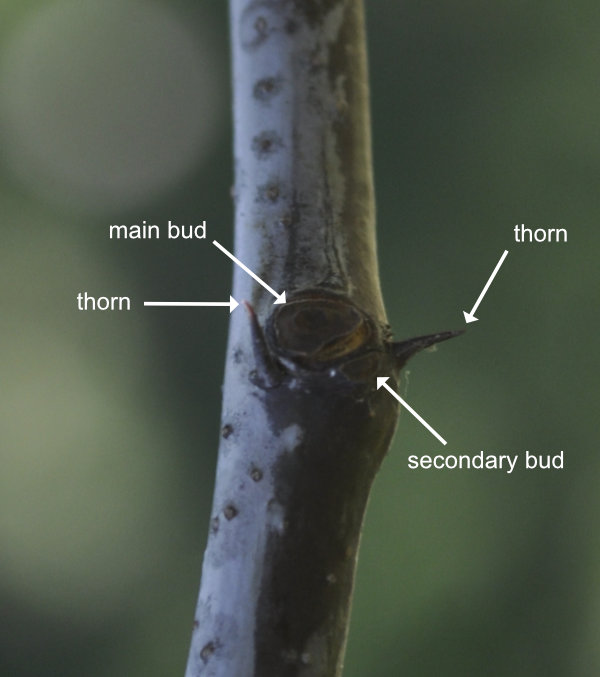

Jujube nodes are unusual in that they contain two bud types: a main bud, and a secondary bud (Fig. 5):

Redlands branch node with a main bud, a secondary bud and two thorns

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

And to mess with your head still more, whether such buds have strong or weak vigour determines the type of branch that will develop from them.

Pretty much every tree you’re familiar with has main branches and sub-branches that resemble each other despite age and location on the tree. But jujube trees really complicate things by having four different branch types: primary (extension) branches, secondary (non-extension) branches, fruiting mother branches, and fruiting branchlets!

The permanent primary extension branches are the ones that determine the shape and size of the tree. These branches are formed by terminal (end), strong, main buds which shoot each year and for many years to extend the tree’s overall structure and shape.

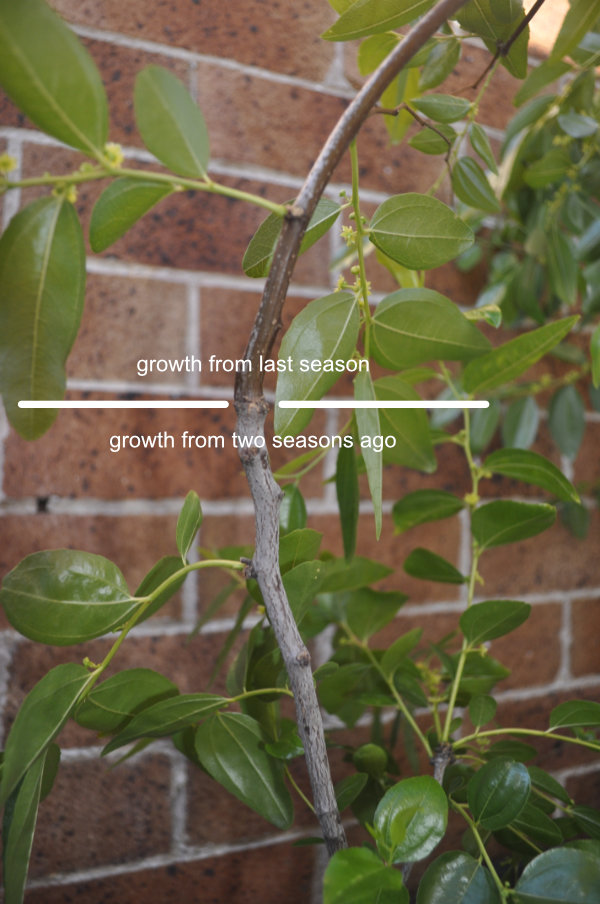

You can differentiate each yearly shoot extension along a branch — and thus age the wood — by its colour. Wood that grew two or more seasons ago is a drab grey-brown colour that becomes less brown and more grey with age. This wood also develops more furrows the older it gets (Fig. 6). (Thank you to Adrian for permission to use this photo!)

Old wood with furrows at base of Chico trunk

© Adrianus van Leest

Last season’s wood is a smooth reddish brown. The transition between this and the prior year’s growth is very clear in Fig. 7 below. This wood will eventually become grey and develop furrows as it ages.

Seasonal growth along young Sherwood trunk

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

Current season’s growth is a bright green (Fig. 8).

Current season's growth in rootstock

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

The green will gradually change to the red colour of year-old wood by season’s end the following autumn. Fig. 9 shows this year’s growth on the Li of Fig. 3 above beginning to change colour at time of writing in late spring, 12th November 2019.

Current season's growth changing colour along a Li branch

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

Some years later the terminal bud will weaken, the extension growth will halt, and a terminal fruiting mother branch forms instead of an extended branch.

Thus to summarise what we’ve covered so far: permanent branches are formed from strong terminal main buds, and fruiting mother branches form from weak terminal main buds.

Fruiting mother branches (not to be confused with fruiting branchlets, which we’ll get to!) aren’t only produced by terminal weak buds — they also develop from other bud and branch types which I’ll also get to — but let’s stick with the terminal buds for now as this is already getting complicated!

A fruiting mother branch resembles a pine cone. Like these two on the Ta-Jan in the earlier post that birthed this post (Fig. 10):

Fruiting mother branches on a Ta-Jan

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

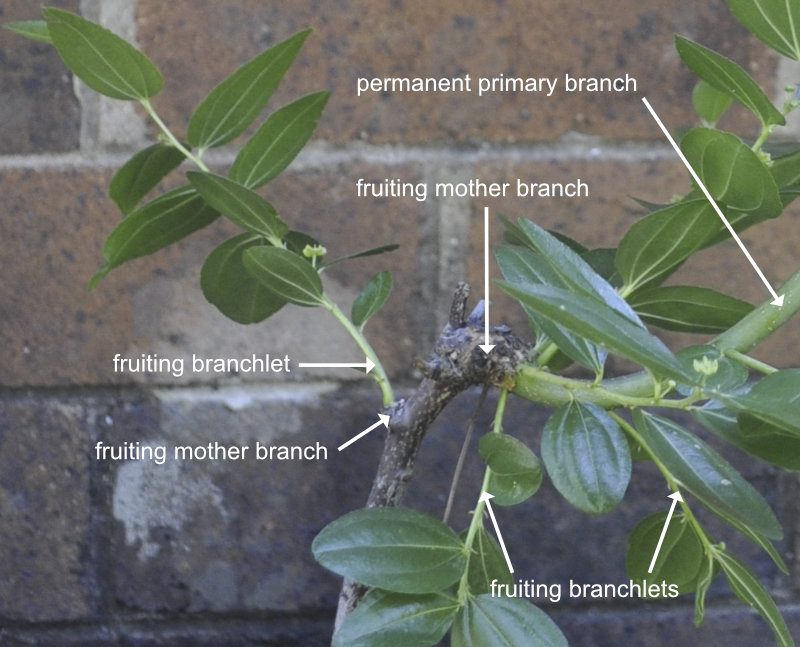

And these two on the same Li in Fig 3 above (Fig. 11):

Fruiting mother branches and fruiting branchlets on a Li

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

And these two on Adrian’s Chico (Fig.12, and thank you again for permission to use this photo):

Fruiting mother branches and fruiting branchlets on a Chico

© Adrianus van Leest

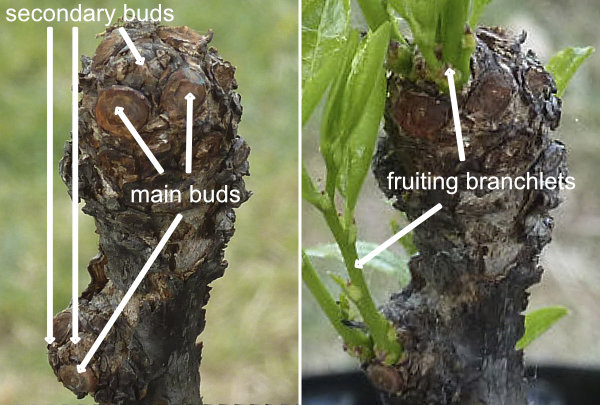

It is not at all obvious that these are branches, is it? Yet they are in fact very compressed shoots with several main and secondary buds on them. The (once strong, now weak) terminal bud of a fruiting mother branch grows ever so slightly each year, producing another cluster of buds that can produce up to ten fruiting branchlets in a whorl. The fruiting mother branch is so named as it is the ‘mother’ of the fruiting branchlets, which are the dedicated branches for the flowers and fruits. The branchlets can vary from 100-300 mm in length (most fall within 120-250 mm in my experience), have alternating leaves on nodes 20-25 mm apart, and typically produce 3 or more fruits. These branchlets resemble compound leaves, but the presence of flowers and fruits show them for what they really are.

Fruiting branchlets are deciduous, and fall off by the following winter. On a small and young tree with little to no trunk/branch development, it is understandable to think your tree has died when you see every one of these little branchlets turn from vivid and healthy flexible green branches, to dried up, dead piles of brown twigs on the ground. Some branchlets do occasionally remain on the tree, but never grow again and come away easily if knocked or removed by hand.

Let’s revist the Ta-Jan. Below in Fig. 13 are the first and last photos of it in this post, side-by-side. Note how the main buds remained dormant while the secondary buds produced fruiting branchlets that growing season of 2017.

Ta-Jan fruiting mother branches with dormant main buds and fruiting branchlets

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

Yet the following year (2018) one of those main buds broke dormancy to produce this shoot, photographed on 10th November, 2019 (Fig. 14). You can tell from the red colour of the uppermost trunk that this shoot developed last season, in 2018. The secondary buds in the lower fruiting mother branches continue to grow fruiting branchlets — which are the same vivid green as all other growth of a current season.

Terminal strong main bud of Ta-Jan broke dormancy to produce extension growth and permanent branch

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

If you go back to Figs. 11 and 12, you’ll see this exact same growth on the Li and Chico. That is, mother branches with secondary buds producing fruiting branchlets, but also where a main bud broke dormancy to produce a permanent primary branch.

But why did the Ta-Jan, Li and Chico all grow this way, while the Lang in Fig. 1 produced a permanent shoot structure from the outset? Here’s a close-up of the trunk of that Lang of Fig. 4 above, on 7th November, 2019 (Fig. 15):

Close-up of a Lang trunk

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

You’ll see a fruiting mother branch at the junction where growth began in 2018. Unlike the Ta-Jan, Li and Chico, this branch simply had a main bud break dormancy in the 2018 season rather than this season 2019, hence the rapid growth readily apparent in Fig. 4. And while the Li in Fig. 4 put on its growth-spurt this year, the Lang has slowed in its extension growth, also shown in Fig. 4. It has instead developed more secondary branch structures.

There is already plenty here to digest, so I will describe these secondary branch structures and other peculiarities of jujube trees in a future post — and there is plenty more to describe when it comes to jujube branch development!

But to wrap up everything covered here:

- Jujube nodes contain two types of bud: a main bud and a secondary bud

- A bud may have strong or weak vigour, and this determines the type of branch that develops

- There are four branch types: primary (extension), secondary (non-extension), fruiting mother branches, and fruiting branchlets

- Terminal, strong, main buds produce the permanent primary branches, which ultimately determine the size and shape of the tree

- Jujube wood is green in its first season of growth (less than one-year-old wood), is red during its second season (one-year-old wood), and subsequently browner then more grey and furrowed with each passing year

- Permanent branch extensions cease when the terminal bud weakens; a fruiting mother branch develops instead

- The (now weak, main) terminal bud of a fruiting mother branch will extend that branch’s growth slightly each year

- Fruiting mother branches contain (usually) dormant main buds and active secondary buds that produce fruiting branchlets

- A dormant main bud can break dormancy in a fruiting mother branch to form a new primary, extension branch

About the Author

BSc(Hons), U.Syd. - double major in biochemistry and microbiology, with honours in microbiology

PhD, U.Syd - soil microbiology

Stumbled into IT and publishing of all things.

Discovered jujube trees and realised that perhaps I should have been an agronomist...

So I combined all the above passions and interests into this website and its blog and manuals, on which I write about botany, soil chemistry, soil microbiology and biochemistry - and yes, jujubes too!

Please help me buy a plant if you found this article interesting or useful!