Pollinators

Update: 5th October 2023

Much thanks to entomologist Katherine Rawson for her help in identifying the ant species in this post to at least the genus level — very much appreciated!

Pollinators are essential to many flowering plants’ reproduction. A flower lures an insect, or a bird or even animals such as bats, to it with its sweet nectar meal, and said insect, bird or animal unwittingly becomes the means by which pollen (male sex cells) meets (and fertilises) ovules (eggs, or female sex cells), which then grow into seeds. (If a fruiting plant, the surrounding ovary develops into a fruit as well.)

(Note to self: put ‘post on how a fruit develops’ on the to-do list too!)

Just to clarify: nectar does not have a direct role in fertilisation; it has an indirect role, in that its sole purpose is to attract pollinators to a flower. Once a pollinator is on a flower, there’s a good chance it will facilitate the movement of pollen to ovules, and fertilise them.

Ants are known pollinators of jujube flowers. This is my favourite jujube photo (and my profile picture) — an ant on a flower in Goulburn NSW, taken by my sister-in-law back in 2014. For an idea of scale, a fully opened flower is about 6 to 7 mm across depending on the cultivar (I said 8 mm elsewhere but have since corrected that after using a vernier scale!):

© Blanca Valle

[Update 5th October 2023: Many thanks to entomologist Katherine Rawson for her help in identifying this ant as a species of carpenter ant (Camponotus sp.) — so good to know, thank you!]

And I finally got around to getting a (lesser) photo of my own, with a (much smaller) Wollongong ant in 2019:

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

Until the zoom lens revealed all, we had no idea those little black ants we have everywhere here have bars on their abdomens! Could any myrmecologists reading this please enlighten us as to the species of the two above? Otherwise the poor things are destined to be referred to as ‘Goulburn ant’ and ‘Wollongong ant 1′ — and I know, as a former microbiologist who freaks out upon seeing ‘a bacteria’ (instead of a bacterium, which is the singular form) that that’s just going to erk you the same way!

[Update 5th October 2023: Thank you again Katherine, who, pending better photos, is quite confident that the little one above is Iridomyrmex bicknelli.]

This ant has some friends about to join him oops, I meant her, as all worker ants are female (as with bees):

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

I can’t see any bars on this one; perhaps it’s a different species? (’Wollongong ant 2′?) The thorax looks different too?

[Update 5th October 2023: Again with the caveat that better photos will help, Katherine suggests that this ant above could be another carpenter ant species (Camponotus sp.).]

So yes, photos of ants apparently enjoying that glistening nectar extruded from the nectary discs strongly supports their being pollinators of jujube flowers!

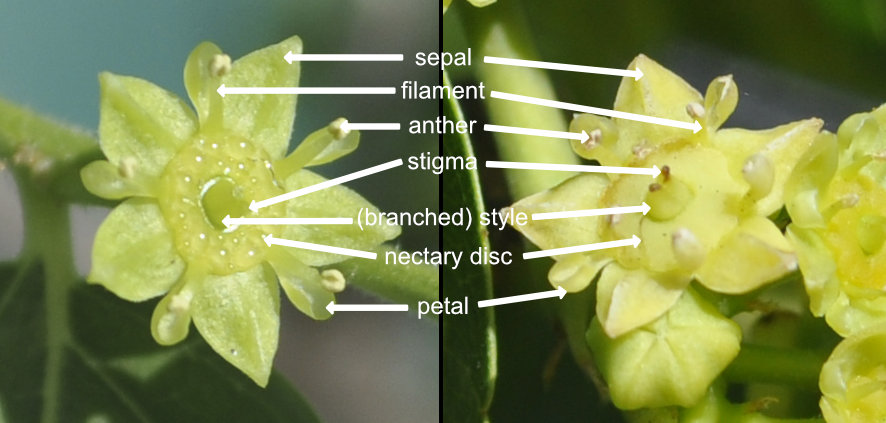

Let’s refer back to this photo from this previous post to visualise how pollination would likely occur:

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

An ant in its travels would move randomly over and across flowers as it seeks a nectar meal. With five anthers arranged evenly around each flower’s perimeter, and so many flowers clustered together and pointing every which way, there’s a good chance that any random ant will pick up at least some pollen released by, and residing on, any one of those anthers it’s bound to brush against en route to any one of those nectary discs.

While an ant is feasting on nectar, and moving between flowers in search of more, it is bound to move across either of the two stigmata of any random flower eventually. The stigma is the pollen receptor, and it together with the style are the means by which pollen reaches an ovule to fertilise it.

Thus while an ant may not necessarily carry pollen from an anther to a stigma on the same flower, it may well carry pollen from any anther of one flower to any stigma of another flower, and the result will be the same — fertilisation of a flower, whichever one that happens to be.

For some months now we couldn’t help but notice an absolute plethora of orange ladybirds suddenly appear in the jujube trees — they were everywhere and the more we looked the more we saw! We had never seen them in such numbers, nor ever seen them on the trees in past years. We eventually identified them as Hippodamia variegata, or the spotted amber ladybird/ladybug/ladybeetle (and thank you once more Katherine for confirming this identification):

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

(The distinctive black and white markings on the head and thorax aren’t evident in this photo unfortunately, but they are there.)

This species isn’t native to Australia, but has spread throughout the world via their native Palearctic region. (I had never heard of such a zone until reading up on these beetles!)

They were quite possibly brought here intentionally, as they love to eat crop pests such as aphids. Apparently they can eat up to 50 aphids a day each! (Please note: that link is incredibly slow to load owing to the hi-res images, but those are stunning and well worth the wait!)

So out I went whilst writing this, a day after taking the previous photo, to get a much better photo showing the head and thorax markings, and discovered we actually have two orange-and-black species loving our trees! The things you discover with a zoom lens…

This beetle is Coccinella transversalis, or the transverse ladybird/ladybug/ladybeetle.

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

This species is native to Australia, and the greater Malesia region (another area I never knew existed until reading up on ladybirds!).

Yet instead of munching aphids (none of which I’ve ever seen on jujube trees), both these species seemed to love nothing better than to spread across a flower and stay there. I knew they weren’t pests, but what were known predators of insects doing on these flowers instead of roaming the branches in search of prey? Could they be, um, eating that nectar instead?

I do feel it’s plausible that these little delights are indeed pollinating the flowers by way of helping themselves to the nectar.

Ants are well-known to ‘milk’ aphids for their favourite honeydew food the aphids secrete. Do ladybirds also taste this honeydew when eating aphids and have a bit of a sweet tooth accordingly? I suspect jujube nectar satisfies something for them, as so many of them are either sprawled across an entire flower, or moving between flowers. We hardly see them on the leaves or branches.

Could jujube nectar taste like aphids’ honeydew? This could explain why ants frequent the flowers so much — I rarely see bees around these flowers, though they are often around the parsley going to seed nearby. And this could also explain the attraction of ladybirds to the flowers.

The beetles’ size and bulk would certainly facilitate movement of pollen from anthers to stigmata efficiently. Look at how close the transverse labybird is to the anther in that photo above for example, and how big it is compared to the flower. It probably marched right over the furthest (not visible) anthers to get to the nectary disc, collecting pollen on its underside as it did so. And right in the middle of that disc, underneath the beetle, are the stigmata.

I’d be very surprised if these two ladybird species, at least, aren’t pollinating those flowers.

I say beg, borrow or even steal these gorgeous beetles for your own nefarious ways — I reckon your trees will thank you!

About the Author

BSc(Hons), U.Syd. - double major in biochemistry and microbiology, with honours in microbiology

PhD, U.Syd - soil microbiology

Stumbled into IT and publishing of all things.

Discovered jujube trees and realised that perhaps I should have been an agronomist...

So I combined all the above passions and interests into this website and its blog and manuals, on which I write about botany, soil chemistry, soil microbiology and biochemistry - and yes, jujubes too!

Please help me buy a plant if you found this article interesting or useful!