Photo Journal: Transplant Shock

While waiting for the terminal buds of the 2020 Ta-Jan blogging tree to do — or not! — as predicted, I thought a post on transplant shock an interesting diversion this week.

Back on the 22nd September 2020 I did a photoblog post showing the two years of root growth of a three-year-old Li, Ta-Jan, Lang, and Chico. I was re-potting them in Air-Pot containers anyway, so why not share what they look like beneath the ground — plenty of people would love to know this! (There were also a three-year-old Sherwood and Si-Hong similarly photographed and repotted, but not shown in that post, and a one-year-old bare-rooted Li, Li #2 and Shanxi-Li similarly potted — more on all these below.)

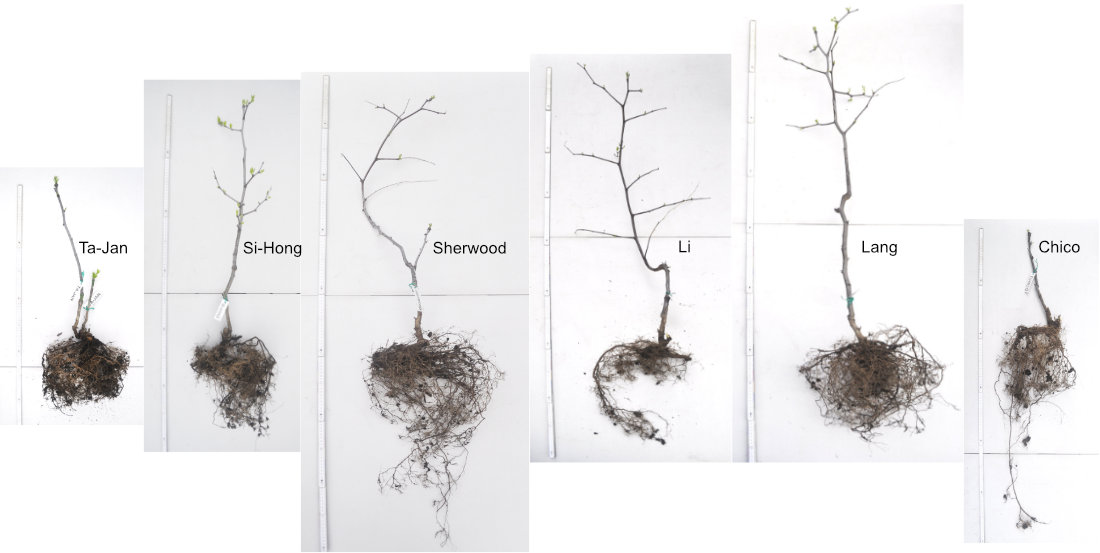

Here is a composition of all six three-year-old trees side-by-side (the one-year-olds were not photographed):

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

These six are in Air-Pot containers in this very order, which has some importance as we’ll see.

This photo reveals two big no-nos to the initiated: one was that the trees were very much leafing up, and the other was that the roots had all potting medium removed.

These are very much frowned-upon practices and not at all recommended. (And I’ve since updated the Photo Journal: Two Years of Root Growth post to make this more clear.)

Firstly, deciduous trees, if they are to be disturbed at all, are always best replanted whilst dormant to minimise stress. Dormant trees maintain just enough low-level cellular respiration to keep alive, and are not actively acquiring external sources of energy, water or nutrients. This is why a dormant tree can be kept out of the ground for a while, so long as the surrounding environment is cool and moist (not wet). A cool, moist environment both prevents the roots drying out as well as signals to the tree that it is still enduring winter.

Secondly — for any non-dormant plant — the roots themselves should be as minimally disturbed as possible when replanting, and ideally surrounded by as much soil as possible. This is partly to protect (as much as possible) the very delicate root tips, as these are the only parts of a root that grow and develop root hairs. And partly to maintain (as much as possible) the very important rhizosphere and microbiome that may have taken months and years to establish.

(Dormant trees can tolerate root disturbances, and even root trimming, as they rely on stored energy reserves to break dormancy in spring. This energy fuels the growth of new leaves and roots, which allows the plant to again photosynthesise and uptake water and nutrients.)

But, science! I really wanted to show just how tough these trees are compared to many other deciduous species, hence wasn’t phased in the least about the late potting-up. And there was no other way to show the rootballs without removing a good chunk of medium first.

So, having photographed and repotted six three-year-old trees (and that is the subject of another post eventually), and potted three one-year-old bare-rooted trees, I gave them all a good drink every couple of days, and thought nothing more of it.

All nine trees carried on looking healthy and thriving over the next week, and then, overnight, the Ta-Jan looked like this on the 29th September:

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

The Si-Hong and Sherwood nearby were similarly sick-looking, and I was paranoid enough to see very early signs of ‘the affliction’ I may otherwise have not noticed in the Lang and Li also nearby. Yikes! What was going on? At first glance (from a distance) it looked, from the stunted-looking, dark green leaves that it was a phosphorus deficiency. Which I’d never seen, mind you. And which made no sense anyway, as these trees had not only recently been given a hefty dose of phosphorus-rich chicken manure, they were barely in leaf enough for any deficiencies to show up. On a closer look it was more apparent that these leaves were shrivelling up and dying.

But why? Time to think!

My immediate next thought was that the potting medium was somehow responsible. All nine trees had literally been potted up in an identical fashion all within hours of each other, which was a significant common factor. But again, that didn’t really make sense as I had used the same homemade concoction as here, and was quite happy with it last year (I did tweak it slightly, which I shall write about later, but that tweak wasn’t to blame).

The first thing to do was to assess all nine trees individually and look for clues that way.

Of the three-year-olds, the Ta-Jan, Si-Hong and Sherwood were by far the sickest looking. The Li looked a tiny bit upset, the Lang a little less again, and the Chico was powering on having not skipped a beat at all. All three of the one-year-olds showed no ill-signs whatsoever.

Good, I could rule out the potting mix! (And the Air-Pot containers for that matter!)

But I did have another clue: age. I didn’t exactly have a statistically significant sample size, but it was clear that the only ones affected were the three-year-old trees. But only half of them badly — and why those three in particular? And why was the Chico completely unaffected? From this came another clue, in that the severity of symptoms seemed to follow the order they were arranged, as in the first photo above: Ta-Jan worst, Chico least affected.

Could it be location then? The three-year-olds were, after all, all together in a narrow, closed-in area along a brick wall, with the sickest-looking Ta-Jan closest and most exposed to the entrance, the Chico furthest away and least exposed, and the others in-between and in order of severity of symptoms. The one-year-olds were also together but much further away, and in fact in a completely different area that was more open and exposed.

Still another clue to ponder was that the younger trees were not as leafy as the older ones, and were barely out of bud.

And then it hit me — just three days prior we had had 100.1km/h WNW gales! As the forecast had been for ‘only’ 50km/h winds I hadn’t prepared ahead of time with additional watering to get them through.

These poor trees were suffering transplant shock, and those strong winds were enough to tip them even these tough trees a little over the edge. They had just lost two years’ worth of rhizosphere and microbiome and had had to adjust suddenly to this quite dramatic change, just as photosynthesis and growth coming back online. The strong, drying winds simply added to this stress. The younger trees, on the other hand, were less developed, less established, and could cope better with those conditions.

For a photo journal, this post has become rather wordy! Time for a bunch of photos to enter.

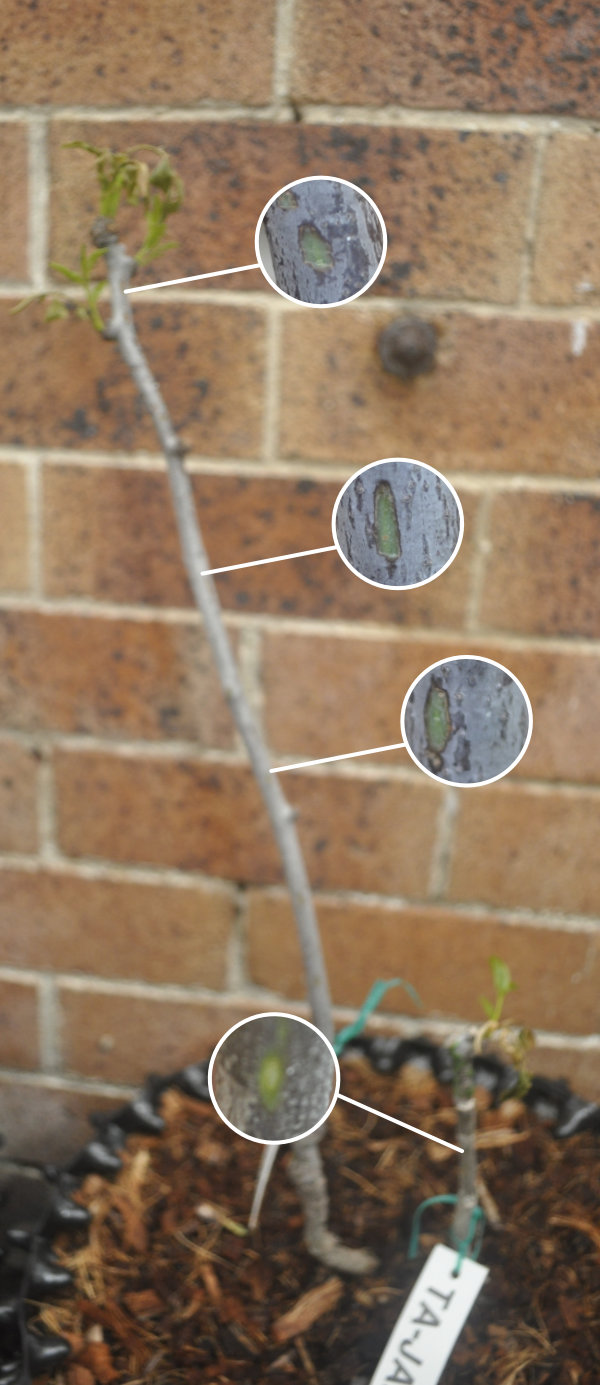

As mentioned earlier, the Ta-Jan, Si-Hong and Sherwood by far showed the worst signs of stress, and of the six would have taken the brunt of the winds roaring down that closed-in area. But the Ta-Jan being the first in line wasn’t the sole reason it suffered the most. It is also the only one with two trunks:

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

And gently scraping the bark along those trunks revealed these sap colours (my apologies for the blurriness of the tree and the lowest sap-colour insert):

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

The lowest insert on the short trunk shows a vivid green colour, while progressive scrapings up the tallest trunk shows a more dull green. The vigorous leafy growth hid the fact that sap flow has not yet fully returned to this particular tree. Scrapings of the other five trees revealed the vivid green sap was right to the very tip of each of those trunks, despite most of them being much taller. It’s likely that sap flow in the Ta-Jan is slower to return to full strength on account of two trunks needing to be supplied.

Once it was clear that it was ‘only’ transplant shock and a good dose of heavy winds behind ‘the affliction’, there was nothing to do but keep the water to them as normal, and otherwise let them recover on their own.

Yes, some species would probably never recover from such an experience, but these are jujube trees and tough as nails, and there is very much a happy ending!

All the photos below were taken today, the 13th October 2020.

This is the tip of the tall Ta-Jan trunk, before the dead leaves were removed:

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

and the same tip after removal of those leaves, and it looks better already!

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

Here is the tip of the short Ta-Jan trunk after removal of dead leaves:

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

And new growth everywhere:

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

Si-Hong:

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

Sherwood:

© Optimate Group Pty Ltd

The Li never looked any worse than this on the outside — though the leaves are still small and I suspect it is still recuperating on the inside. These leaves were present at the time of the winds:

© Optimate Group pty Ltd

Likewise for the Lang:

© Optimate Group pty Ltd

And the little Chico, completely unscathed, has put on a whole bunch of flower buds in the meantime:

© Optimate Group pty Ltd

On the subject of flower buds, all six were developing these around the time of the winds — there are two in the Lang photo above though they may not be visible. Unfortunately the Ta-Jan lost its with the dead leaves, but the others still have green buds, and importantly, are on still-green stems and surrounded by half-green leaves. (I say ‘half-green’ because many of the leaves stayed a healthy green colour in the half closest/attached to a stem, while the other half shrivelled and died.)

What are the take-home messages from all of this? Unless it’s for science, stick to repotting deciduous plants while they’re still dormant! And regardless of species, and whether deciduous or evergreen, it’s also a good idea to keep as much of the rootball covered in soil or soil-equivalent as possible, especially for older, more-established trees. And if you must repot as they are greening up, be very mindful of weather extremes at all times!

But also, these trees are still tough!

About the Author

BSc(Hons), U.Syd. - double major in biochemistry and microbiology, with honours in microbiology

PhD, U.Syd - soil microbiology

Stumbled into IT and publishing of all things.

Discovered jujube trees and realised that perhaps I should have been an agronomist...

So I combined all the above passions and interests into this website and its blog and manuals, on which I write about botany, soil chemistry, soil microbiology and biochemistry - and yes, jujubes too!

Please help me buy a plant if you found this article interesting or useful!