The Importance of Soil pH to Plant Health

Last week’s post examined the chemistry behind pH, where we saw how pH is a measure of the concentration of hydrogen ions (H+). High concentrations of ions create an acidic environment, and the measured pH has a value below 7. Low concentrations of ions makes an environment more alkaline, and the measured pH has a value above 7. A value of 7 is neutral, neither acidic nor alkaline.

This post will look at the significance of this to plant health.

Why is pH Important in Soil?

Soil may appear to be a lifeless clump good for keeping plants upright, but beneath the surface is an abundance of activity affecting that plant life directly and indirectly. That activity is driven by chemical reactions, many of which are influenced by hydrogen ions. In terms of plant health, some of those reactions will be affected in a good way, and some in a bad way.

For example, the concentration of H+ in the soil can affect:

- the availability of nutrients to plants,

- the amounts of nutrients held in soils (ie not leached away),

- toxicities, and

- microorganisms (bacteria and fungi)

Let’s go over each of those in turn.

The Availability of Nutrients to Plants

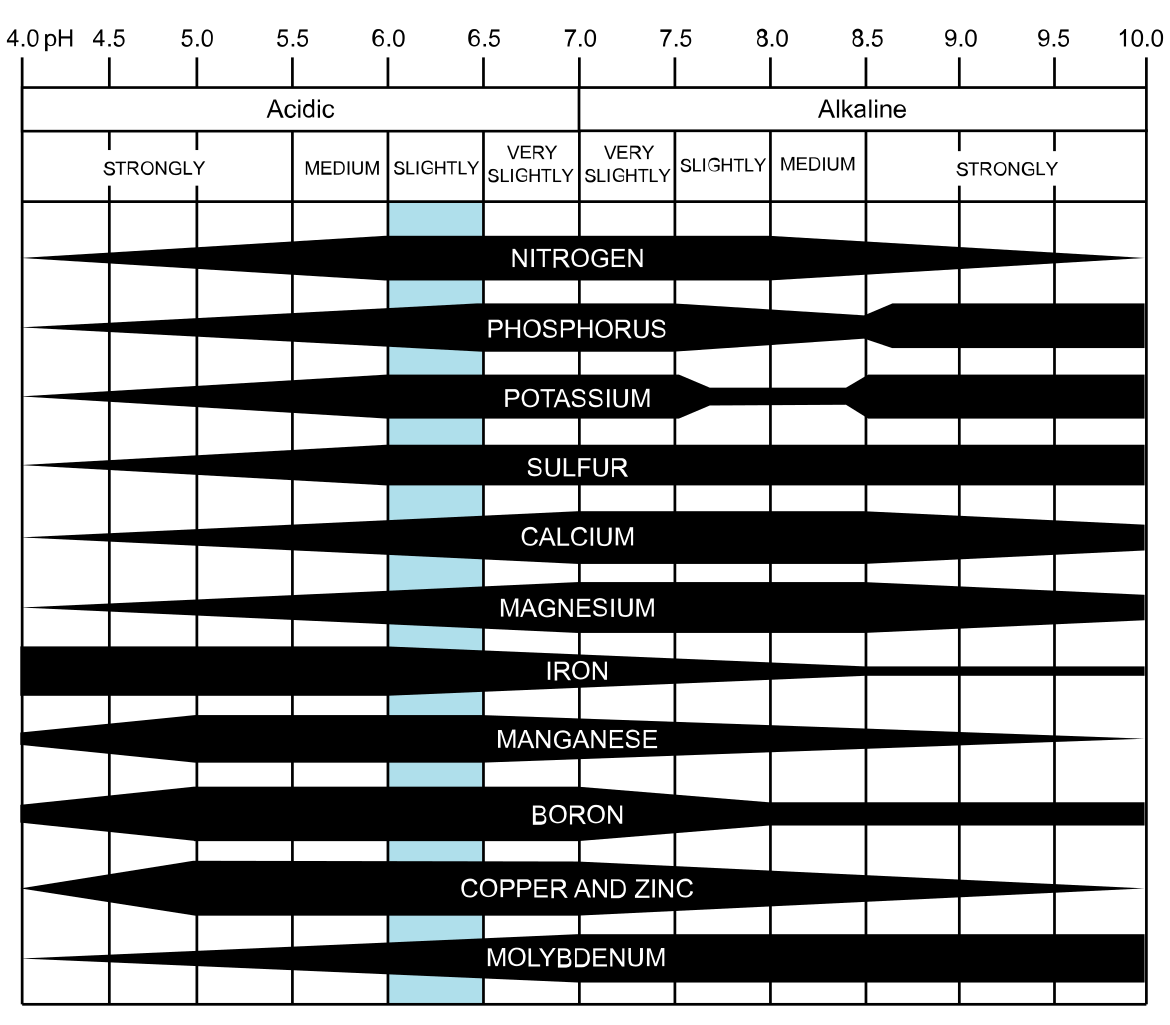

A nutrient may exist in abundant amounts in a soil, but if a plant can’t access it for whatever chemical reason prevents it, that nutrient may as well not be there. It simply is not available to the plant. The following diagram sums this up especially well (the thicker the bar the more available the nutrient):

Attribution: CoolKoon [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]

Here it’s pretty clear that soils within a pH range of 6-7 have the greatest availability of all nutrients, which is why pH 6.5 is cited so often as the ideal for growing pretty much everything. But even so, many plants may still grow well enough at a pH as low as 5.5 even if not optimal for them.

The effect of pH on nutrient availability is more critical when nutrients are at sub-optimal amounts in a soil. Changing the pH can increase availability to a plant, but if the soil is already deficient then any boost will be short-lived.

On the other hand, a soil with large amounts of a nutrient — or one continually supplied with nutrients — may still be able to supply a plant enough of what it needs despite limitations imposed by pH.

The Amounts of Nutrients Held in Soils

Please be mindful of the difference between ‘availability’ and ‘amount’ of a nutrient. ‘Availability’ is what a plant can access, and ‘amount’ is the quantity in a soil. To take the extremes, a nutrient may be present in a small amount, with all of it available to a plant, or a nutrient may be present in a large amount with none of it available to a plant.

Clays and humus are the particles in soils that hold nutrients in soils. (We’ll cover soil structures in future posts.) Soils rich in clays and humus have increased nutrient retention and decreased leaching. And these clays and humus hold increasing amounts of nutrients as pH is raised.

Toxicities

Toxic levels of substances can rise as pH drops. Increasing concentrations of H+ ions can release increasing amounts of those substances into the soil water where they become available to plants. Manganese toxicity begins at pH 5.5, followed by aluminium toxicity at pH 5. Not all soils contain enough manganese to poison plants, but many soils can reach toxic levels of aluminium at low pH as this element is typically common in soil. (It’s actually the third most abundant element in the earth’s crust, after oxygen and silicon, measured in parts per million by mass.)

Microorganisms

Microorganisms include viruses, bacteria and fungi, and these are abundant in soils. Some are harmful to plants and cause disease. Most are beneficial in that they break down organic material and make this more accessible for plant uptake. All are affected by pH, and different species, as with plants, vary in their preferred pH ranges. We’ll be going into much more detail about microorganisms and their roles in soil in future posts.

We’ve now covered the [chemistry of pH], and shown its importance to plant health here. Over the next few weeks we’ll be discussing the very medium at the heart of this: the soil itself!

About the Author

BSc(Hons), U.Syd. - double major in biochemistry and microbiology, with honours in microbiology

PhD, U.Syd - soil microbiology

Stumbled into IT and publishing of all things.

Discovered jujube trees and realised that perhaps I should have been an agronomist...

So I combined all the above passions and interests into this website and its blog and manuals, on which I write about botany, soil chemistry, soil microbiology and biochemistry - and yes, jujubes too!

Please help me buy a plant if you found this article interesting or useful!